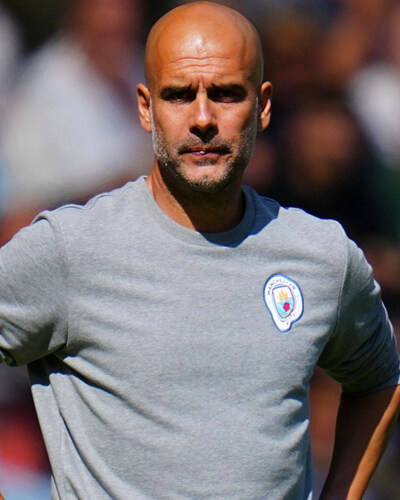

Josep “Pep” Guardiola (b. 18 January 1971), the Catalan

football manager and former player, is one of the most consequential coaches of

modern football. His career, stretching from his formative years under Johan

Cruyff at FC Barcelona to his managerial dominance at Barcelona, Bayern Munich,

and Manchester City, has produced a body of work of such aesthetic coherence

and tactical sophistication that it is often described in near-religious terms by admirers. Widely regarded as one of the greatest football managers of all time, he holds the record for the highest number of consecutive victories in three different top European leagues.

From his earliest days as a player, Guardiola was marked not

by innate genius of touch but by a burning intensity of will and control.

Cruyff, who made him the pivot of Barcelona’s “Dream Team,” saw in him a player

of rare intelligence and command rather than flair: “He reads the game better

than anyone else on the pitch” (Cruyff 1999, p. 84). Guardiola’s leadership as

a midfielder was not democratic but directive—he imposed rhythm, shouted at

teammates, gestured incessantly, and, as teammate Ronald Koeman recalled,

“always wanted everything perfect” (Koeman 2004, p. 112). These early

testimonies reveal the young Guardiola’s

Strong and

Valued F:

the constant exertion of personal will to dominate and shape events. His

authority was not derived so much from emotional appeal or charisma but from

the unrelenting energy with which he imposed his conception of order on those

around him.

This same exertion of force continued and intensified in his

managerial career. Guardiola’s formative influences are important because they

show the origin of his methodological self-image. After his time as a player in

Cruyff’s Barcelona system, became a coach who insisted on the same organizing

principles: occupation of space, numerical superiority, coordinated pressing

and transitional patterns. As Xavi Hernández and other contemporaries have

noted, Guardiola’s football is an explicit programme of positional rules rather

than improvisatory flair; its point is to render success predictable by making

situations recurrent and therefore trainable (see technical exegesis in

Perarnau and other accounts of Guardiola’s Barca and subsequent iterations).

Perarnau’s research into Guardiola’s Barca — and the manuals that have followed

from his school — underline a managerial logic: principles (strict positional

frameworks) are formulated and then instantiated through constant repetition in

training sessions (rondos, positional exercises), video review, and

meticulously prescribed roles in match moments. This biographical and

methodological continuity is not accidental; it indicates a personality

orientation that values procedural mastery and seeks to publish that mastery in

reproducible form. Furthermore, his style of football, founded on positional

play (juego de posición), represents a systematic ordering of space and

movement designed to subordinate every opponent’s will to his own

This account provides evident for

Strong and

Valued

L as well as

F. To work out the positioning of these two functions

in Guardiola’s

Ego Block, we must ask which is

Stubborn and

Bold,

and which is

Flexible and

Cautious. To answer this question, we

can look at the extent to which he is willing to adapt his principles to

achieve results. For example, when Guardiola adopted different personnel at

Bayern (Lahm, Alaba) he imposed his usual demand for central territorial

control as principle but adapted his positional logic to invert full-backs and

elicit midfield overloads, while relying on pragmatic coaching drills and

rehearsal to render those roles executable. Similarly, at Manchester City the

occasional “parked-bus” pragmatism in specific matches demonstrates that his

system accepts tactical exceptions when the practical exigency demands them (Ojwang,

2025). This demonstrates that pragmatism for him is the tool that ensures the

will actually obtains results rather than rather than a betrayal of principle. He

preserves the underlying principles he values (e.g. control of space,

overloads, positional discipline) even when the outward shape of his team

changes. Here,

L and

P seem to be acting in balance, which is consistent

with

Cautious and

Flexible L2 working together with

P8.

Guardiola repeatedly frames his work not merely as coaching

but as a quest for domination: “I want to win. I want to play serious. I want

to be effective” (BrainyQuote, 2025). When asked about his players’ mindset, he

declared that “they have something inside – some fire – to compete or else we

would not be here,” (Mumford, 2024). His own reflection on defeat is even

sharper: “I want to suffer when I don’t win games… I want that when the

situation goes bad, it affects me” (Martinez, 2025). Such statements do more

than express ambition; they signal the characteristic

SLE drive for

victory as a battlefield of wills: whatever the opposition, whatever the

context, the aim is to

use whatever resources exist to secure the upper hand.

Guardiola’s willingness to restructure his squad, overhaul training regimes,

and enforce demanding standards from day one (for instance, seating plans,

dietary restrictions, language rules at Barcelona) is recorded in Guillem

Balagué’s biography and points to a managerial disposition that does not merely

adapt but

pushes the environment itself until it conforms (Balagué,

2012). At Manchester City, his acceptance of “park the bus” situations – not as

a defeat of principle but as a pragmatic deployment of force to win –

reinforces the idea that the will to win is non-negotiable even if the

prototype form temporarily surrenders. In short, his leadership style reads as:

challenge → dominance → adaptation of means. That progression is emblematic of

F1:

the primary impulse is bold will-to-win; logical and technical tools follow as

servants to that aim.

If Guardiola’s will to win is non-negotiable, his willingness

to expand the range of possibilities is subordinate to it. So far in his managerial

career he has constantly experimented—turning full-backs into midfielders,

midfielders into false nines, goalkeepers into sweepers. “I cannot stay still,”

he confessed. “I have to move, to find new ways” (Guardiola quoted in Wilson

2018, p. 211). Yet these experiments were never motivated by a love of

possibilities for their own sake, but by necessity—each new idea serving to

maintain competitive dominance. Here the boundary between

L2 and

I3 becomes

visible. Guardiola’s

I3 manifests as a limited and instrumental

relationship to possibility. He does not ideate freely but rather deploys new

ideas under the pressure of circumstance. When a pattern ceases to deliver

control, he searches not for aesthetic novelty but for a new mechanism to

re-establish mastery. Hence his tactical innovations—such as the use of

inverted full-backs at Bayern or John Stones’ hybrid role at Manchester

City—emerge not as speculative visions but as calculated responses to

disruptions in structural equilibrium (Honigstein 2017, pp. 202–04).

The established structure we have established of

F1,

L2,

I3 and

P8 predicts Bold and Stubborn

E6 in Guardiola’s

Super-Id

block, and this is indeed evident. On the touchline he is famously

animated—shouting, gesturing, crouching, celebrating with ecstatic abandon. He

is, in Martí Perarnau’s phrase, “a man of explosions” (Perarnau 2016, p. 203).

His team talks oscillate between tears and fury, as seen in Amazon’s All or

Nothing: Manchester City (2018), where Guardiola’s half-time addresses shift

from roaring invective to pleading encouragement. This emotional volatility is

not affectation but mobilisation; it activates his environment and sustains his

intensity. Whereas his leading function (

F1) imposes will, his

mobilising function (

E6) injects vitality into that will, giving it

human temperature. The result is a leadership style in which reason and passion

are fused in perpetual oscillation. Players often describe his talks as

transformative—David Silva recalled that Guardiola’s words “made you feel like

you could run for ten more minutes even when you were dead” (Silva quoted in

The Guardian, 2019).

Guardiola’s relationship to relational and interpersonal

dynamics, by contrast, has repeatedly exposed an

R4 blind spot. He is

known for his inability to maintain long-term emotional equilibrium within

teams; after three or four seasons, he tends to exhaust both himself and his

players. At Barcelona, his relationship with Zlatan Ibrahimović disintegrated

in mutual hostility, with Ibrahimović later accusing him of lacking “the

courage to look me in the eye” (Ibrahimović 2011, p. 238). At Bayern, he

quarrelled with club doctors, notably Hans-Wilhelm Müller-Wohlfahrt, leading to

a public rupture (Müller-Wohlfahrt 2017, p. 189). His interpersonal management

oscillates between intense involvement and abrupt withdrawal, reflecting a

difficulty in gauging the personal boundaries of others. Guardiola’s leadership

is charismatic but not relational: he inspires devotion through energy, not

empathy. Players often describe him as magnetic but draining. Philipp Lahm

observed that “his talks could last hours, and you would leave the room

exhausted but also somehow distant from him” (Lahm 2017, p. 156). The

combination of emotional over-investment and relational misjudgment is

diagnostic of

R4: an area of blind weakness in an otherwise

hyper-competent personality.

If Guardiola’s

R4 manifests in his difficulty

sustaining interpersonal equilibrium, his

T5—his

Suggestive

function—emerges in his relationship to time, continuity, and meaning.

Guardiola’s football is defined by obsessive attention to the present moment,

to immediate perfection rather than long-term legacy. “I don’t think about the

future,” he told Martí Perarnau. “I think about the next training, the next

pass” (Perarnau 2014, p. 31). Even his most elaborate tactical systems are

conceived for immediate dominance rather than enduring inheritance. There is no

sustained contemplation of destiny or purpose beyond the current battle. His

suggestive desire for

T manifests indirectly in his fascination with

history and art—his repeated visits to museums on away trips, his admiration

for figures such as Cruyff and Bielsa—but these are borrowed temporalities, not

intrinsic ones. Guardiola intuits the importance of meaning and legacy but

cannot construct them from within; he seeks them through others’ narratives.

The interpersonal and temporal weaknesses,

R4 and

T5,

combine to produce a particular pattern of burnout and renewal. Each managerial

tenure follows the same trajectory: initial conquest through force and system;

gradual erosion of relational harmony; exhaustion; withdrawal. Guardiola’s

self-awareness of this cycle is limited. After leaving Barcelona he admitted,

“I was empty, drained, I needed to rest,” but soon afterwards he plunged into

Bayern, repeating the same pattern (Honigstein 2017, p. 15). His inability to

project himself into a stable future or to manage emotional bonds beyond the

short term keeps him in perpetual motion. He survives by reinventing contexts

rather than by reconciling conflicts.

Guardiola’s

S7—his

Ignoring function—appears

in his pragmatic yet unromantic attitude toward bodily comfort and physicality.

His attention to players’ conditioning is meticulous but instrumental; it

serves tactical goals rather than sensory pleasure. Guardiola himself lives

ascetically: he neither smokes nor drinks, he walks or cycles rather than

drives when possible, and his aesthetic environment is minimalist. Former

assistant Domènec Torrent described him as “incapable of switching off, but

capable of functioning perfectly on four hours of sleep” (Torrent quoted in

Balagué 2012, p. 203). This detachment from bodily indulgence shows that

sensory balance is neither valued nor problematic; it is managed automatically

and dismissed when irrelevant. acts as a buffer allowing him to sustain the

extremes of

F1 and

E6.

Taking everything into account, the evidence reviewed in

this article demonstrates

F1,

L2,

I3,

R4,

T5,

E6,

S7, and

P8, making Pep Guardiola a clear example of

the

SLE type of information metabolism.

To learn more about

SLE, click

here.

If you are confused by our use of Socionics shorthand, click

here.

References

Balagué, G. (2012). Pep

Guardiola: Another Way of Winning. London: Orion.

BBC Sport. (2020). “Kevin De Bruyne on Working with Guardiola.” BBC Sport,

14 May 2020.

Cruyff, J. (1999). My Turn. Barcelona: Ediciones B.

Honigstein, R. (2017). Pep Guardiola: The Making of a Supercoach.

Munich: Knaus.

Ibrahimović, Z. (2011). I Am Zlatan. London: Penguin.

Koeman, R. (2004). My Life in Football. Amsterdam: Nieuw Amsterdam.

Lahm, P. (2017). The Game: The Secrets of Football. Munich: Droemer.

Ojwang, G. (2025). Why Guardiola’s Inverted Fullbacks Changed Football Forever. The Medium

Pep Guardiola quotes. BrainyQuote. Retrieved 2025.

Martínez, A. (2025). ¿Especial yo? Cadena.

Müller-Wohlfahrt, H. (2017). Mit dem Herzen sehen. Munich: Droemer

Knaur.

Mumford, J. (2024). My players motivate themselves, says Guardiola. Manchester

City.

Perarnau, M. (2014). Pep Confidential. Barcelona: Córner.

Perarnau, M. (2016). Pep Evolution. Barcelona: Córner.

The Guardian. (2019). “David Silva: Inside Pep’s City.” The Guardian, 12

May 2019.

The Telegraph. (2017). “Pep Guardiola: I Will Die with My Football.” The

Telegraph, 3 March 2017.

Wilson, J. (2018). The Barcelona Legacy. London: Blink.

Comments

Post a Comment