Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (born Junker Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, 1815-1898) was chancellor of Prussia and later Germany. He is best known for his achievement of unifying the various German states (completed in 1871), which he continued to govern as Chancellor until his dismissal by Kaiser Wilhelm II (EIE) in 1890.

One of the most interesting things about Bismarck was his lack of real power. As a mere chancellor, his position was completely at the mercy of his benefactor, the King of Prussia and later German Kaiser, Wilhelm I. Wilhelm always had the final say as a somewhat absolute monarch, and could override or fire his chancellor whenever he wished, and in addition to that, any specific domestic law that Bismarck wanted needed to be passed by the Reichstag. Despite this, Bismarck’s contemporaries, including his friends and enemies (of which he had many) widely considered him to be a dictator.

This is because, despite his limited power, Bismarck was keenly aware of how to use what little power he had to get whatever he wanted. Bismarck managed to unite and rule Germany through sheer force of will. And it was through his forceful and temperamental personality that Bismarck maintained his nearly unchecked power over Germany for nearly 20 years. Kaiser Wilhelm I himself once remarked “It is difficult to be Kaiser under Bismarck.”

Whenever Bismarck faced opposition, whether it was real or perceived, his first instinct was always to fight to enforce his will. Bismarck believed that open conflict had a sort of ‘cleansing’ effect. Examples of this could be seen throughout his time as Chancellor of Germany, most notably his attempt to crack down on the Catholic church (Catholics were the majority in Southern Germany) which led to suppression of Catholics themselves and Catholic practices, known as the 'Kulturkampf' or 'Culture struggle'. Other notable examples include during the 1848 revolutions, which Bismarck opposed, when Bismarck gathered the peasants of his estate to march on Berlin to defend the monarchy against the revolutionaries (though the Prussian officers he met when arriving rejected his plan and instead told him to simply gather supplies). Bismarck's constant conflicts with the Landtag (Prussian parliament) resulted in the House of Deputies declaring that they could not work with him, and the King responded by dissolving the Diet and allowing Bismarck to introduce laws suppressing freedom of the press early in his chancellorship. Bismarck also opted for a military method to unite Germany, starting wars with Denmark, Austria, and France to do so. Furthermore, he established a series of anti-socialist laws to forcefully suppress the Socialist party as much as he was legally allowed. According to Bismarck’s worldview, conflict was necessary to achieve what one wanted, best encapsulated by his now famous “iron and blood” speech.

In September 1862, when the Prussian House of Representatives were refusing to approve an increase in military spending desired by King Wilhelm I, the monarch appointed Bismarck Minister President and Foreign Minister. A few days later, Bismarck appeared before the House's Budget Committee and stressed the need for military preparedness to solve the German Question. He concluded his speech with the following statement:

“The position of Prussia in Germany will not be determined by its liberalism but by its power [...] Prussia must concentrate its strength and hold it for the favorable moment, which has already come and gone several times. Since the treaties of Vienna, our frontiers have been ill-designed for a healthy body politic. Not through speeches and majority decisions will the great questions of the day be decided—that was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849—but by iron and blood”

This speech sent shockwaves through Prussia’s parliament, in which liberal members held a plurality of the seats, and created a mini-crisis that almost saw Bismarck losing his power immediately after acquiring it, as many in Prussia’s government pushed for Wilhelm I to fire him. Luckily for Bismarck, Wilhelm refused, and in the following decade Bismarck would make good on his promise to use iron and blood to achieve his goals.

Bismarck in general was always aware of his power and leverage in any situation. One of his many ways of maintaining control over Wilhelm I was to threaten to resign, and thus no longer offer his political expertise to the management of Prussia/Germany. Another one of Bismarck's methods was feigning a temper (which was believed by everyone because Bismarck on many occasions showed a very real and very vicious temper), such that no one would be willing to risk ending up on his bad side.

Throughout all of Bismarck’s life, fighting to achieve his goals, conflict with opposing factions, a desire for power and desire to subordinate others, were all the most common themes present. This is enough to make F1 quite obvious. It really is no wonder he was, and is, often referred to as ‘The Iron Chancellor’.

Bismarck’s worldview is also indicative of his sociotype. Bismarck was a radical conservative, believing in maintaining royal supremacy and a strict social hierarchy. Maintaining royal power was one of Bismarck’s main goals after unifying Germany, with his other goals being the maintaining of his own power and creating a united German identity. While it is unsurprising that Bismarck would seek to preserve the social hierarchy in Germany since Bismarck himself was a Junker (Prussian nobility), his genuine belief in the King's divine right to rule and the fervor with which he defended royal and aristocratic power makes it clear that his hierarchical values come from a genuine internal motivation, rather than solely pragmatic concern for his own position in society (though maintaining his position in society certainly played a role in Bismarck's ideology). This hierarchical worldview is indicative of valued, and likely confident L blocked with F. Bismarck also had a strong ability to use laws and legal loopholes to his advantage, such as when Bismarck, as well as King Wilhelm, disliked the budget put forward by the Landtag, so rejected it and despite the lack of legal precedent, asserted that he would be able to use the previous years budget to run the government since a new budget had not been agreed on. Bismarck's skills at legal manipulation also point toward strong L.

Despite his conservative leanings, Bismarck was not a strict ideologue. He was willing to compromise on his views in pursuit of his goals. For example, although he would have preferred an authoritarian royalist state, Bismarck introduced universal male suffrage to gain a political advantage in the North German Confederation (the northern states joined Prussia prior to Bismarck’s unification of the South) in 1867. Though pursuing the Kulturkampf to reduce the power of the Catholic church, Bismarck would end the Kulturkampf and ally with his former Catholic opponents in the German Centre Party to fight against the Socialists. To fight against the Socialists, despite being reactionary, Bismarck would introduce one of the most advanced welfare states in Europe to gain support from the working classes that would have likely gone to the Socialists instead. For Bismarck, there were few hard lines, and policies were tools to be used to resist opposing ideologies and power blocks, rather than be ends in and of themselves. This is best summarised by one of Bismarck’s well known quotes, “Politics is the art of the possible, the attainable — the art of the next best.” This is enough to say conclusively that Bismarck used F and L with great confidence but also with notable flexibility in his use of L, most consistent with L2. In addition, Bismarck’s ability to change tactics and compromise his ideological pursuits when needed is indicative of some effective I usage, but unvalued, seeing as it was only used when necessary. The adaptive nature of Bismarck’s use of I, combined with the complete lack of value placed on it for its own sake, is most consistent with I3.

While Bismarck was easily able to rely on F and L to navigate the politics in Germany and push through his agenda, one of the most interesting facts that sets him apart from many other authoritarian leaders was his lack of overt grandiosity. While Bismarck certainly had a high opinion of himself and knew that, by uniting Germany, he had forever changed world history more drastically than the vast majority of leaders, during his time in power he was not one to advertise this fact often. He did not tend to give grand speeches and in fact was a somewhat poor public speaker (except for in debates, of course, where he was quite skilled). He also lacked charisma in the conventional sense of the word. Though many were attracted to his very powerful personality, he did not project an appealing image nor make others feel good through charm.

At least, this was how he acted while in power. After his fall from grace and dismissal by Wilhelm II, Bismarck briefly retreated to isolation in his estate, before eventually getting back into politics indirectly through giving interviews, releasing secrets, and playing at what his son Herbert called 'pseudo-politics'. He also began writing his memoirs. During this period between his downfall and his death, he began going on tours through Germany where large crowds gathered to see the ‘Iron and Blood Chancellor’ in person, cheering him on. During these events, Bismarck would enjoy reveling in all of the praise and attention. He would then give actual public speeches meant to create an emotional effect, rather than for purely pragmatic and political purposes. For most of his life, Bismarck operated purely for political gain and acquisition of power, but later in life became more extroverted and engaged in the social and emotional atmosphere, consistent with E6.

As one would expect from Bismarck’s lack of emotional awareness, his behavior regarding his personal relationships left much to be desired. Bismarck’s quick temper and vindictiveness would often lead to him mistreating his loved ones, causing him much shame and regret once he had calmed down. One minor example was when Bismarck, in a fit of anger, hit his dog. Shortly after, his dog died of natural causes related to old age (not due to Bismarck’s mistreatment), causing Bismarck to break down in tears over having mistreated the dog he loved so close to its death. A much bigger example would be when Bismarck used his power to threaten to change German primogeniture laws to disinherit his eldest son Herbert, thereby preventing him from marrying the woman he loved due to many perceived personal failings, such as her divorce and because she was from a family of Bismarck’s political rivals. This turned Herbert into a cynical alcoholic and he never recovered, causing Bismarck much guilt throughout the rest of his life.

Additionally, Bismarck could only enforce his political will through his power and leverage, since he was often unable to get others to join his side personally due to his reputation for having a poor moral character. While beloved by the masses, particularly after his dismissal by Wilhelm II, Bismarck often made a poor impression on the individuals he interacted with in politics, which would prove a massive hindrance to him when trying to push his agenda. This all would seem to make R4 a good fit. Biographer Jonathan Steinberg said of him, while describing how he was forced to resign by Wilhelm II, as..."Having crushed his parliamentary opponents, flattened and abused his ministers, and refused to allow himself to be bound by any loyalty, Bismarck had no ally left when he needed it."

Lastly, Bismarck’s legacy of a united, royalist Germany as the most powerful country in Europe would come crashing down after his death in the world wars, partially due to Wilhelm II’s expansionist ambitions and the relative incompetence of Germany’s early 20th century leaders. Bismarck had created a system in German politics and foreign policy where only he, by nature of his genius, was capable of managing the various conflicting interests. No else one understood the systems that Bismarck had created, such as the League of the Three Emperors, which formed an alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia, an alliance that made no logical sense due to the extreme and explicit hostility between Austria and Russia over control of the Balkans. In fact, sometimes even Bismarck didn’t understand them himself, but managed to keep these systems and policies going despite the seeming impossibility, thanks to his pure political skill, but despite being praised for his genius, the German state and foreign policy that Bismarck oversaw was always a house of cards, and without the “genius statesman” keeping it up, it was destined to come crumbling down.

Strangely, for someone as obsessed with his legacy as Bismarck, he did not see this turn of events coming until long after his fall from power. It is often said that Bismarck’s legacy crumbled so soon after his fall from power because Bismarck could not envision a world without himself. Bismarck’s desire to protect his legacy and complete inability to do so despite his immense power seems most indicative of T5.

Further indication of T5 can be seen throughout Bismarck's time in power in how he pushed through policies or systems in the moment to gain more immediate power and leverage which would later come back to disadvantage him in the future. His establishment of universal suffrage is a perfect example of this, as it helped him gain an immediate political advantage, but in the time of the German Empire, would come to be a hinderance as liberalism became more popular in other German states and its popularity would continue to grow under Bismarck's reign.

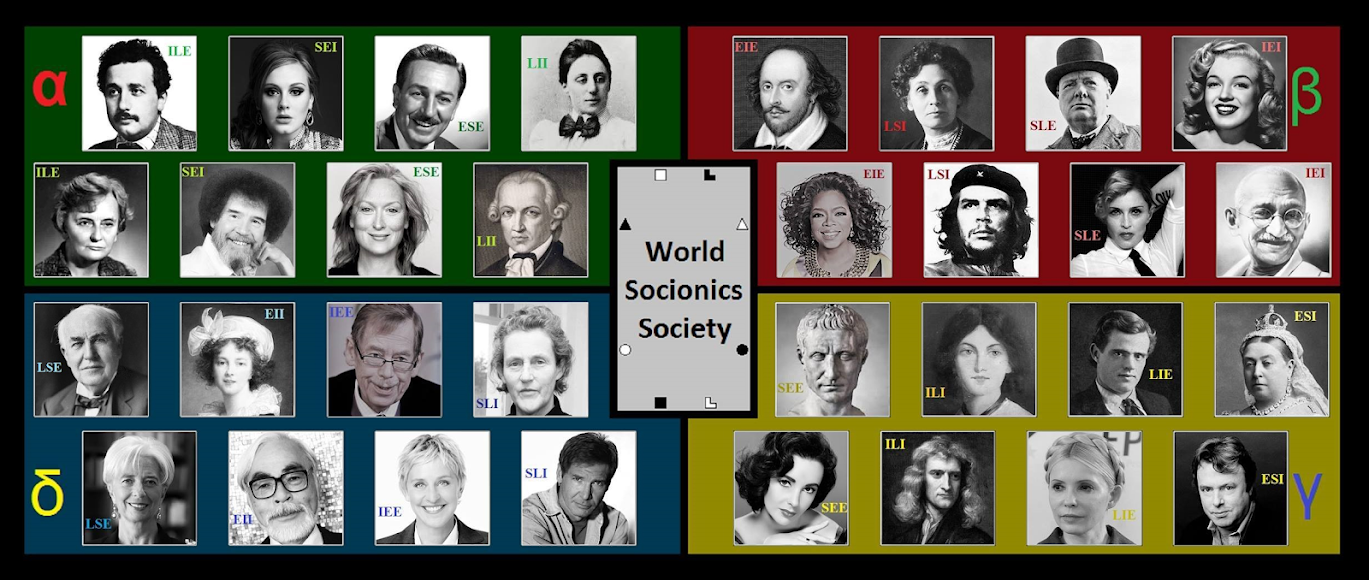

Having argued for Bismarck’s use of F1, L2, I3, R4, T5, and E6, I find it impossible to see Bismarck as any type other than SLE.

Sources

My main source was Jonathan Steinberg's biography 'Bismarck: A Life